Having grown up in rural regions, I’ve found myself glued to coverage of the bushfires raging throughout Australia at the moment. It has been emotionally stressful, even as an observer.

Several million hectares of land has been burnt by the fires. Whole communities have been cut-off, the residents and visitors of towns have been forced to seek shelter on beaches, and in some cases, get themselves into the water to try to find refuge from the fires. Elements of our armed forces have been mobilised, including the navy to evacuate particularly isolated communities.

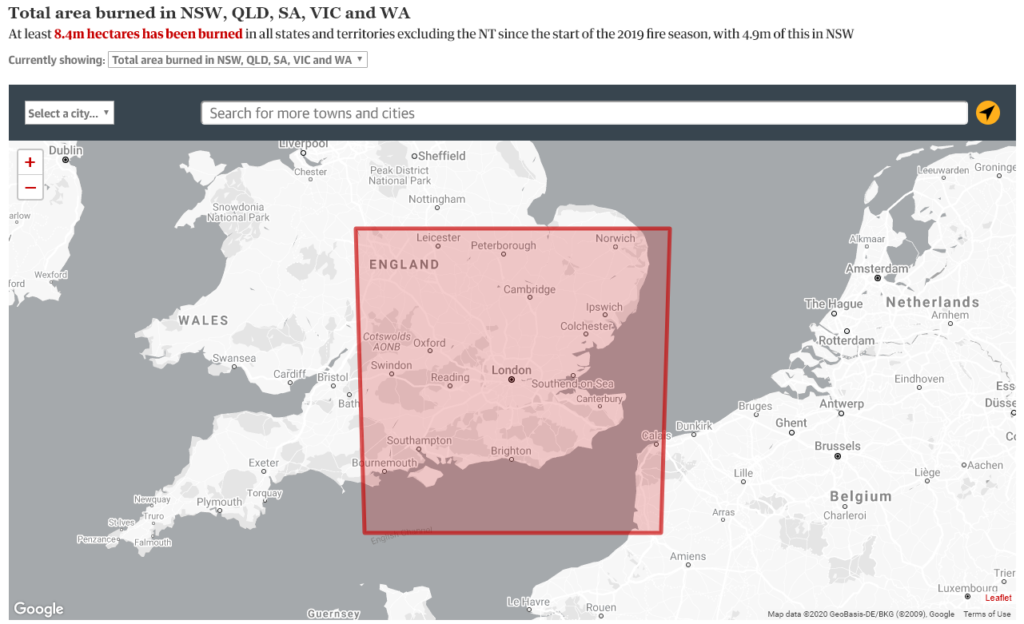

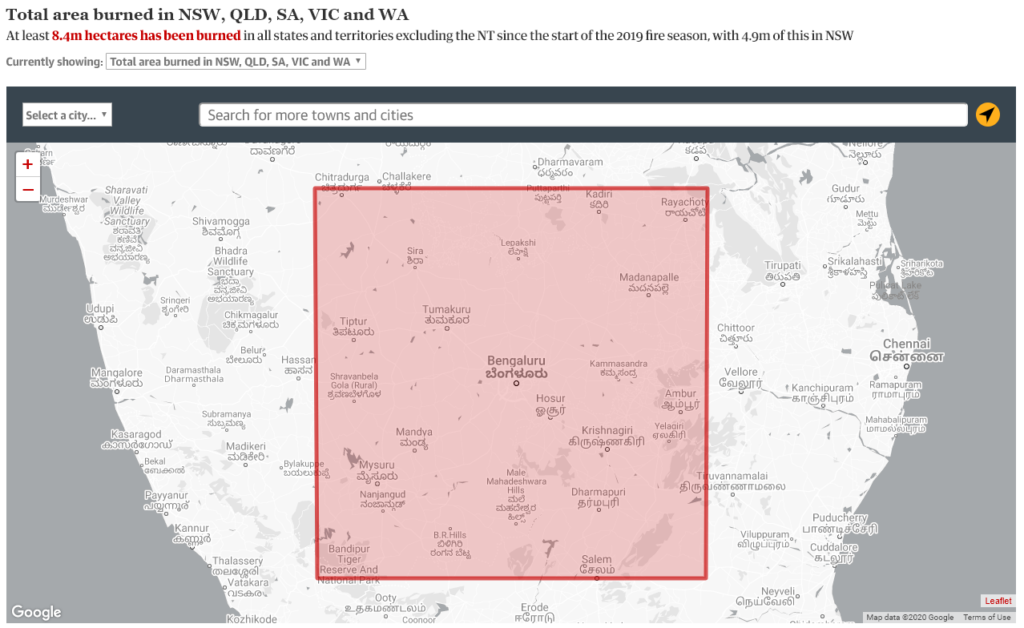

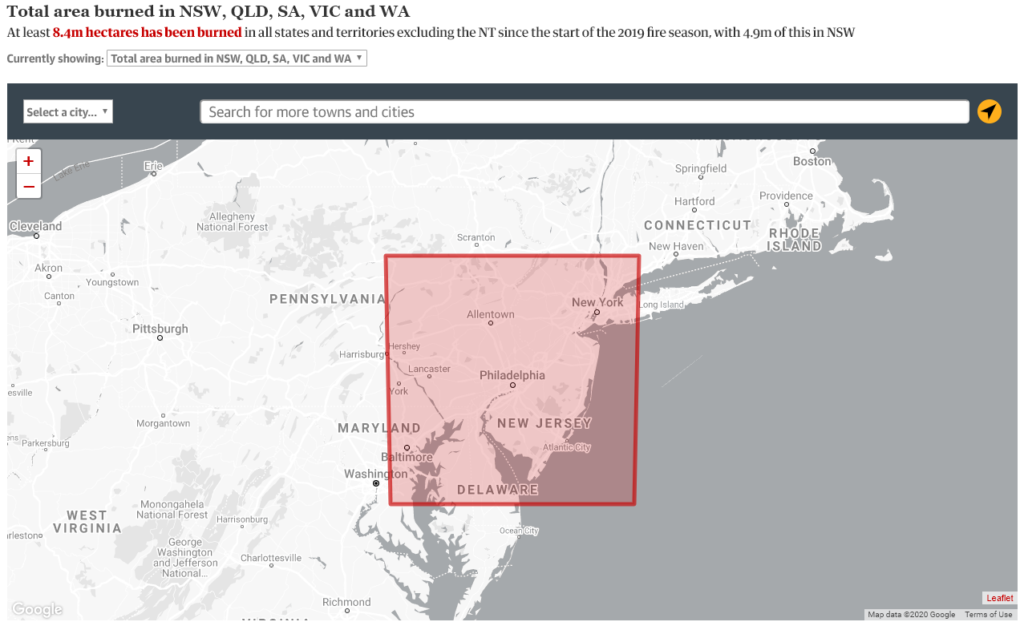

The Guardian as of 7 January states at 8.4 least million hectares (=20.76 million acres, or 32,433 square miles for US readers) have been burnt out. They have an interactive map that helps you understand what that means. Using that map and picking a few countries other than Australia, you get views like:

Australians are becoming familiar with pyrocumulus clouds – clouds generated by fire systems that start generating their own weather, and in particular, lightning storms. Of course, that’s in addition to firestorms so intense they generate fire tornadoes that can flip 10-tonne trucks. Earlier in the bushfire season, there were a host of videos like the one below showing crowning, where the fires race up to the tops of trees and start spreading that way.

At current count, well over two thousand homes have been destroyed. (This doesn’t include non-dwelling buildings, which is a much higher number.) It seems insensitive to say this, but the loss of human life is still remarkably being measured in the double-digits – it seems incomprehensible that the numbers aren’t much higher, and much must be attributed to the heroic efforts of the volunteer firefighters. It’s expected the insurance bill will easily top out over a billion (it’s already at $700 million and rising), and quite likely go higher.

It was estimated at the end of 2019 that close to a half-billion animals (birds, reptiles, native mammals and livestock) have been killed in the bushfires. That’s just in New South Wales (admittedly the largest section of the fires). Since then, The Guardian has revisited those figures with the same experts, and the number across the country is conservatively estimated to be in excess of a billion animals. The expectation is that it will drive multiple species into extinction. The effects on the koala population of the country have been devastating alone, with fires ripping through preserves/habitats in NSW and South Australia. (The largest koala population – and healthiest – was to be found on Kangaroo Island. While hard figures are currently impossible to come by, I’ve seen estimates that two-thirds of the 50,000+ population would have died, and many others left severely injured.) Volunteer firefighters in multiple states have reported the visceral horror and trauma of hearing koalas shrieking as they burn alive.

I mention all this because it is imperative to understand this is not just a regular fire season. This is a portent of what is to come, due to climate change.

Because of the level of catastrophe, it’s not possible to discuss this without mentioning some pertinent political details. These are:

- We have a conservative government that has repeatedly blocked or done its utmost to curb climate change activities (including repealing a carbon tax).

- The government has been under sustained pressure for cheating as a way of meeting emissions reductions (‘carrying over’ credits – i.e., an accounting sleight-of-hand).

- Our federal government (and to a lesser degree, our main opposition party) has been fervently supporting coal and exporting large amounts of it, thereby increasing our global contribution to climate change – this includes billions of dollars of subsidies for coal mines that will have a significant negative impact. (For example, while the federal government has committed two billion dollars in bushfire relief aid, that’s dwarfed by the over four billion dollars they’re providing to the Adani coal mine.)

- A coalition of ex fire and emergency chiefs had for months been trying to meet with our Prime Minister to discuss their serious concerns about the likelihood of a catastrophic bushfire season but had been rebuffed on multiple occasions.

- Our scientific community had been warning for years that climate change was going to cause more extreme events in Australia and that we had to be prepared for ever-expanding bushfire seasons.

- Even during the bushfire crisis, we’ve had a government backbencher going on UK TV and radio making outrageous claims that there’s no link. (That backbencher, I’d note, is also a member of the “Parliamentary Friends of Coal” bipartisan group. As whackjob denialists are so fond of saying, you do the math.)

- We’ve also had a former conservative prime minister do an interview in Israel decrying the “cult of climate change”. Again, during this catastrophe.

It’s worth noting, particularly in the last point, that traditionally, our bushfire seasons have been during the hottest parts of summer – January/February. (December has usually been a ‘mild’ period for bushfires for Australia.) It is not uncommon to hear “the worst is yet to come”.

An aside…

If you wish to argue that climate change isn’t real – that it’s some great conspiracy, then I’d humbly suggest that you may very well lack the cognitive functions needed to operate successfully in the modern world, and you would be better off selling all your things and becoming a recluse for the rest of your life. Arguing against climate change is like arguing the earth is flat, or gravity is just an imaginary concept. Only unlike those examples, the consequences of working from this position can be dangerous to society. (In short, I’m done with arguing with denialists.)

So what’s all this got to do with backup and recovery, or data protection? Well, there’s the obvious considerations that there will be a lot of affected businesses, but I’m not going to go there. What genuinely concerns me at this point is that we’re seeing just how little a country in the G20 has prepared its key infrastructure for the inevitable challenges posed by climate change.

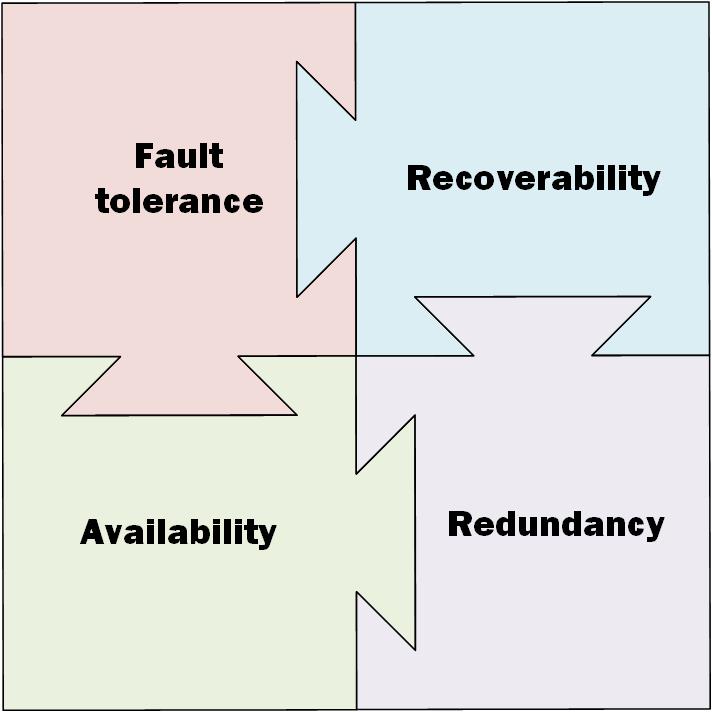

You may remember a while ago I talked about the FARR model for data protection: fault tolerance (e.g., RAID), availability (e.g., clustering), redundancy (e.g., site failover), and recoverability (bringing back what is lost). This doesn’t just apply to data protection, and it’s clear from the Australian bushfire season thus far that Australia’s infrastructure is not fit for purpose in an environment that humans have made increasingly hostile to humanity and its tools.

In short, what politicians and the public used to decry as “gold plating” in infrastructure is probably going to become the norm if we’re to build and maintain essential services that can survive the inevitable consequences of climate change.

Here are just a few examples:

- Australia Post suspended mail delivery in Canberra, our country’s capital city because the air quality was too dangerous for its staff.

- Air quality has regularly been recorded at hazardous levels in other cities, including Sydney, and more recently Melbourne.

- Indeed, smoke from the fires travelled as far as Chile, and ash and dust have been falling on New Zealand glaciers.

- Multiple outdoor events in major cities have been called off or rescheduled due to the air quality issue.

- Rail systems between the Blue Mountains and Sydney will be out of action for months while critical repairs are performed. This will have a daily impact on roads, carbon emissions and the economy, given the number of commuters who would use that line daily.

- Power was cut to sections of the south coast of NSW. This affected both power and telecommunications.

- It’s worth noting that the National Broadband Network (NBN) replaces conventional copper-based home phone lines with more advanced systems that require power to operate.

- NBN effectively advise the solution to this is to keep a charged mobile phone nearby. That’s not so handy when the power outage takes out the mobile phone towers, too.

- Power and network outages have impacted the banking networks, too. ATMs and EFTPOS systems have been down in a number of locations.

- A number of regions have been encouraged (or even ordered) to evacuate, which led to considerable hassles as people try to buy fuel but find service stations can only take hard cash:

At Batemans Bay, petrol stations on the Princes Highway are either closed, or only accepting cash, because EFTPOS machines are down. But some ATMs are also down, making it impossible to get cash.

Australia’s bushfire towns battle on, despite what they have lost: supplies, power, houses, ‘the lot’. Calla Wahlquist, 1 January 2020, The Guardian.

- This was exacerbated by the number of holiday-makers since the December/January period is our peak holiday season.

- The Federal government has bullishly promoted a “cashless welfare card” – riffing off the common conservative viewpoint that somehow people on welfare spend all their money on things they shouldn’t be. Effectively, it’s a visa card where 75% of the allowance is quarantined for “approved” spending – in approved stores. As you can imagine, cash advances are not possible. One of the cashless card trial areas has been hit by bushfires and affected by power and communications outages. People on welfare in those areas are unable to buy food or essentials because EFTPOS systems are unavailable.

- The connection between the Victorian and NSW power grids was cut. This substantially increases challenges around power network loading and sharing.

There are considerable benefits in a connected society. When I was growing up, my banking was done within a “passbook”. Each credit and debit was stamped or printed onto a sequential line on the card. If I wanted to buy something, I had to present the card at a bank and withdraw the money before going to make the transaction. By the time I went to University, the switch had been made to ATMs and I could just go to a machine-in-the-wall to insert a card and retrieve my cash. A few years after that, EFTPOS became a thing and I stopped having to get money out.

I grew up hearing stories of how my grandfather always carried £6,000 in his breast-pocket, £1,000 for each of his daughters should they ever really, urgently need it – or, as it turned out, for when he died.

I, on the other hand, and many like me would be lucky to have $50 in cash on me at any point in time. Other than buying a coffee, almost all of my transactions are done as electronic ones. “How quaint”, I feel, when I have to pull a card out of my wallet because I can’t tap my watch.

Access to modern services – access to modern information – is held together by strings. Getting access to your money requires power for an EFTPOS or ATM system, and a network behind that system.

Our systems are built on the premise that we’ll usually have sufficient power and networking to achieve what we need, and that outages should be brief. People relying solely on data-based communications (mobile or fixed) would have been substantially cut-off from emergency information during these outages unless they’d had a conventional radio. The NBN may be a perfect example of this. Looping back to a previous link:

“Consider keeping a charged mobile phone nearby in the instance of a power outage.”

What happens during a power blackout? NBNco

That’s essentially the message – since NBN also supplies the landline, if you are going to have a blackout, you need to have a charged mobile phone. That sounds like a plan so long as the cell-towers have power. Indeed, it sounds like a plan so long as the cell-towers exist. (There are sure to be burnt/destroyed cell-towers in this catastrophe.)

An essential design rule in data protection is to consider cascading problems. To me, the simplest demonstrations of designing for cascading problems are:

- We clone our backups in case there’s a physical or access problem with the primary copy

- RAID-6 was invented to give us 2-disk redundancy, to protect against the RAID-5 problem, “What happens if a disk fails during the rebuild?”

I’m not going to pretend I have answers, but I do sincerely hope that when this disaster has passed, and we start to review what happened and what we could do better, a key topic of consideration is how can we make our infrastructure more robust for these situations? And that’s not a question limited just to Australia. All other countries need to start considering this question, too.

Because “she’ll be right, mate” is no longer good enough.

(If you’re interested in making a donation for bushfire relief, there’s a fairly comprehensive list here.)

2 thoughts on “Australian Bushfires show the Precarious State of Modern Infrastructure”