Another day, another data breach. Optus, Australia’s second biggest telecommunications company has suffered a potentially massive data breach, estimating that 9 million or more customers may have been affected. (For reference, the current population of Australia is 25.69 million.)

To this point, Optus seem to have mainly focused on speaking to the media, and have indicated that data stolen is likely to include names, addresses, email addresses and identify details such as driver’s licenses, passports, etc. (The reason for this level of data being on-file at a telco in Australia is a result of government law; to try to prevent burner phones being bought without any traceable information, it’s necessary to provide proof of identification. In Australia, this is usually a “points” system — if you can supply 100 points of identification, you’ve sufficiently proven that you are who you say you are. Non-photo ID, such as your Medicare card number represents fewer points, as do non-government documents, such as University student cards, etc. On the other hand, a valid driver’s license, or a passport, typically represents 100 points. And so, to keep things simple, telecommunications companies ask for your license or passport in order to register a new service.)

So it’s fair to say that telecommunications customer databases are somewhat of a treasure-trove of information, if you like that sort of stuff.

As part of their messaging about the breach (and strenuous denials that it was caused by leaving an unauthenticated API that could query the customer database on the open internet), Optus have issued the insert-standard-text-here warning that: “affected customers should closely monitor for suspicious behaviour in their banking accounts”.

And in this, I find myself thinking of John Proctor’s harrowing statement in The Crucible:

Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life! Because I lie and sign myself to lies! Because I am not worth the dust on the feet of them that hang! How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name!

The Crucible, Arthur Miller.

The circumstances between The Crucible and a modern data breach may differ. Data breaches aren’t witchcraft (however histrionically imagined). Often, data breaches aren’t even all that cunning, relying on a mix of social engineering, known bugs, and yes, insecure programming.

Yet people who are affected by data breaches might feel something similar to John Proctor’s angst: your name might be signed to something you don’t believe in. Or more specifically — your identity can be used against you, and you suddenly find yourself fighting a very large bill.

Ironically, in a modern context, it’s actually easier to change your name than it is to change your other personally identifying information. You cannot, after all, change your date of birth. And few people can afford to just pick up and move to ensure their current address is no longer valid. So once someone has access to that information, and they can add other verification details, such as a driver’s license, it’s very easy for them to prove they are you. And governments/businesses don’t like these details changing.

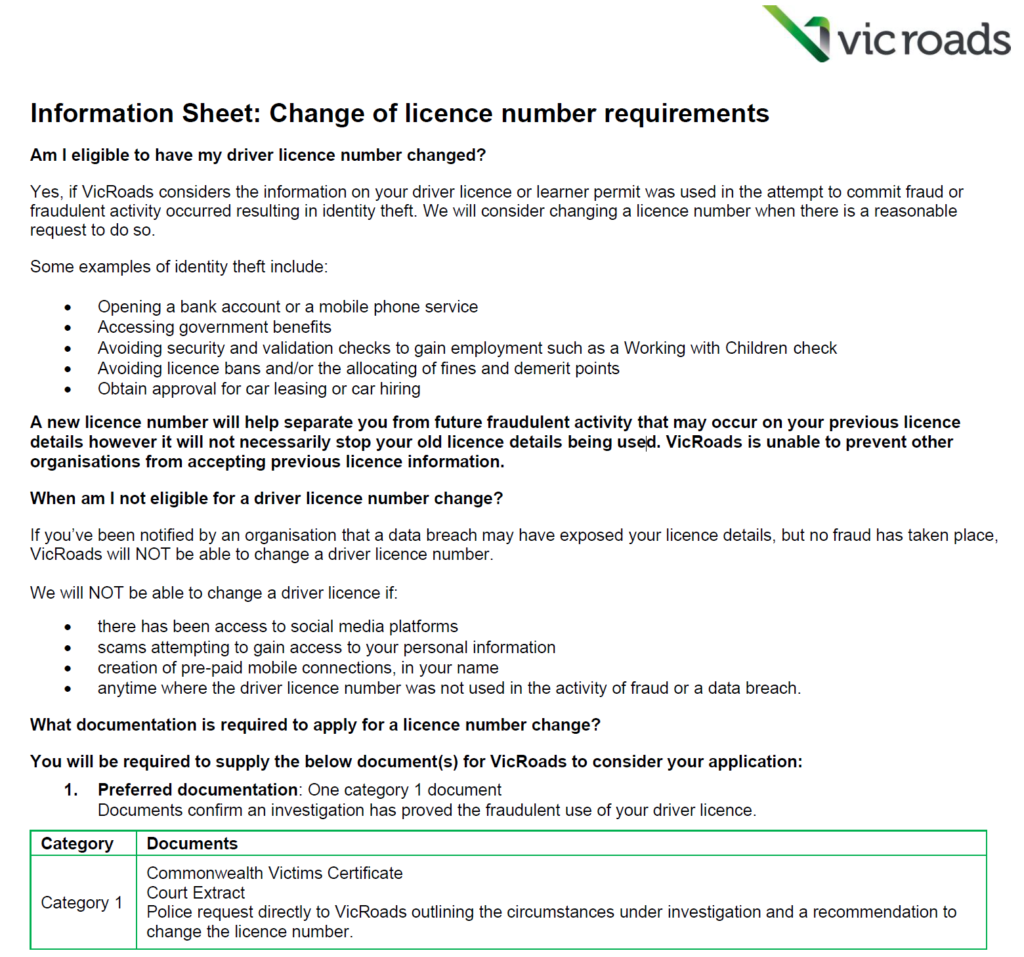

For instance, VicRoads, the state government body responsible for driver’s licenses in Victoria does allow you to change your driver’s license number, but only after you’ve got proof that identity theft has already occurred:

Government bureaucracy is quite the thing, and regularly decades behind what technology can — or should — allow. You can change your license number if and only if you can demonstrate that it has been used to steal your identity already. So while you’re fighting off debt collectors over a car someone else bought in your name, you also have to deal with red tape to change a number that, had you been allowed to change it earlier, could have prevented the whole problem in the first place. As a mathematician friend would say: “Fun. For small values of ‘Fun’.”

And it is funny (and not in a ha-ha kind of way) that in a modern context, governments have toughened data breach disclosure laws, requiring businesses to inform customers as soon as possible if their data has been stolen, but continue to take a lackadaisical approach to citizens who have been affected by a data breach. “Watch for suspicious behaviour”. In these situations, I find myself thinking, why not go the whole hog and offer us thoughts-and-prayers?

Having worked in Enterprise IT for my entire career, I can understand why this is the case. It’s for the same reason that a business will talk about how much they’ve modernised their infrastructure but-please-oh-pretty-please-don’t-look-at-that-NT4-server-sitting-in-the-corner-running-a-workload-no-one-can-ever-afford-to-port-to-a-modern-system. Budget. If it costs two million dollars and a thousand staff hours to change a system, or the customer an extra 12 minutes and $8 every time they do something, guess who pays?

IT systems — particularly in government and large corporate environments — have often evolved with a level of inflexibility. You might be able to change your name1, but can you change core ID details? Not easily. This seems to be something that Optus recognises — after all, it opposed changes to privacy laws to make it easier to have customers request their data be deleted:

The company said in its submission that implementing a right to erase personal data would involve “significant technical hurdles”, and “significant” compliance costs. The costs would far outweigh the benefits, the company said.

Optus first argued in its 2020 submission that giving consumers the power to take direct legal action over privacy breaches could lead to frivolous or vexatious claims, and would not give people greater control over their personal information.

Optus cyber-attack: company opposed changes to privacy laws to give customers more rights over their data, Josh Taylor, The Guardian, 24 September 2022.

(I suspect the least that Optus have to worry about at the moment are frivolous or vexatious claims. Major Australian law firms are, no doubt, already sharpening the verbiage on class action lawsuits.)

The Optus data breach is just one more in a long line of examples that governments and their statutory bodies have to evolve into the 21st century when it comes to handling these situations. They must:

- Allow someone to change relevant personally identifiable information (PII) without the need to prove that a crime has been committed using that detail.

- In the event of there being proof of a data breach, this should be free of charge

- If it cannot be done free of charge, the cost should be passed on to the company with the data breach (yes, crazy idea, I know — forcing businesses to pay for their FUBARs)

- In the event of there being no data breach (i.e., purely precautionary), any fee involved should be an absolute minimum.

- In the event of there being proof of a data breach, this should be free of charge

- Any business or government department storing the same PII data should be required to change it, at the request of the owner, and at no cost or disruption of service. (And of course, this must be done in a secure way that prevents someone from having their PII changed out from under them by an identity thief.)

- Require all businesses to delete PII from their systems as soon as it is no longer required. (I.e., whatever time limits are currently in place aren’t good enough.)

In the meantime, we’ll continue to feel like John Proctor every time a company we do business with is hit by a data breach.

1 thought on “John Proctor and Data Breaches”